No One Will Ever Stop Our Songs

Jerome Rothenberg’s final anthology is his masterpiece: a centuries-spanning tribute to the complexity and contradictions of the American people, whatever illusory border separates them.

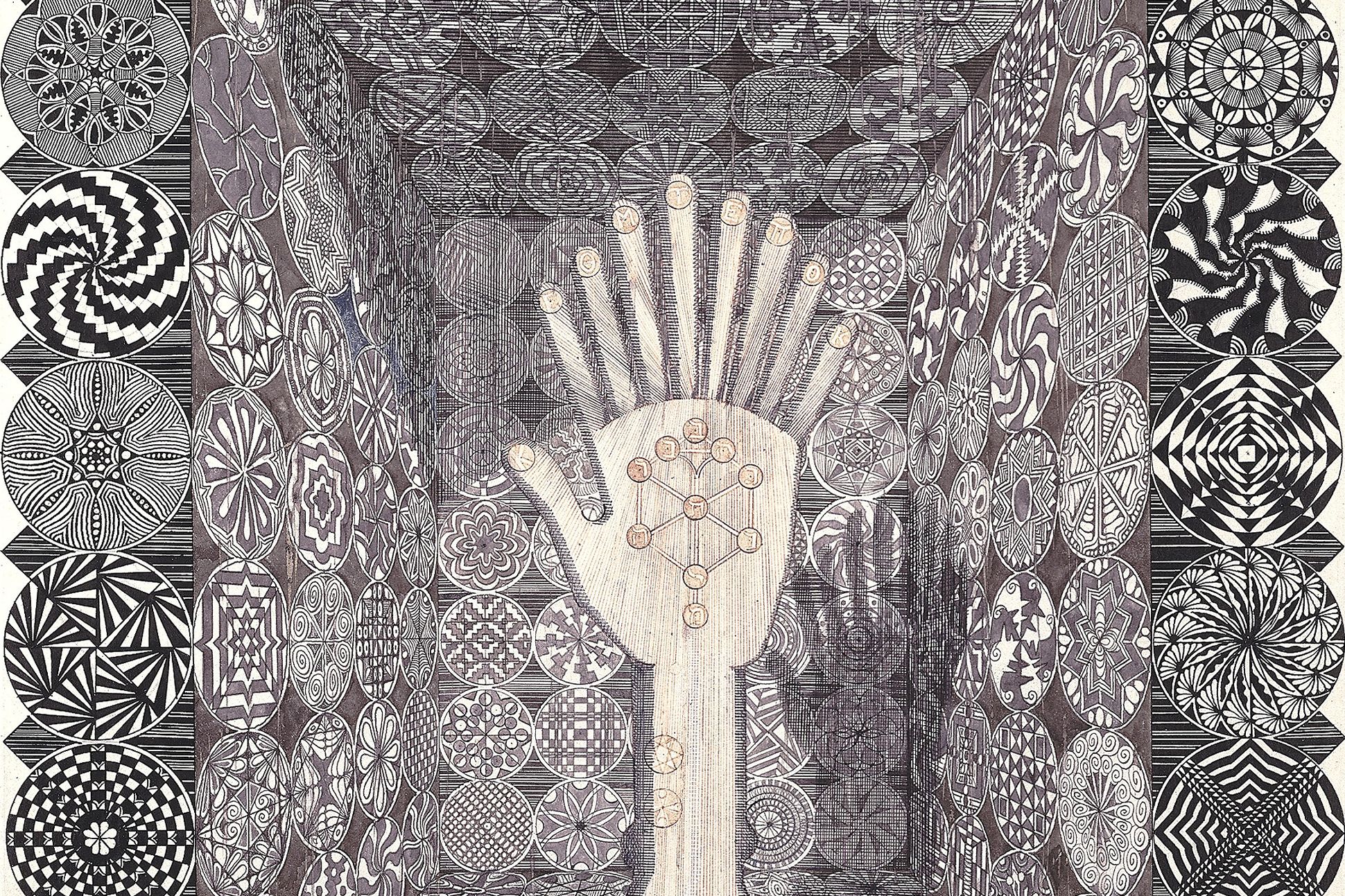

Pedro Friedeberg, “‘Insist on yourself; never imitate. Your own gift you can present every moment with the cumulative force of a whole life’s cultivation; but of the adopted talent of another you have only an extemporaneous half possession.’ —Ralph Waldo Emerson, 1841.” (1964). Smithsonian American Art Museum.

In 1460, according to accounts transcribed more than a century later, the lord Tecayehuatzin gathered a group of cuicapihqui, the poet-philosophers of the Aztec Empire, in the courtyard garden of his palace in Huexotzinco, near the modern-day Mexican city of Puebla. In an arid valley shadowed by the snow-capped peaks of the Popocatepetl and Iztaccihuatl volcanoes, Tecayehuatzin charged these learned men “to discuss the nature of poetry, its origins, & the fate of both poems & poets,” as translators and editors Jerome Rothenberg and Javier Taboada write in their expansive anthology The Serpent and the Fire: Poetries of the Americas from Origins to Present (University of California Press, 2024). A combination debate, reading, and symposium ensued, in which those gathered in this garden of marigold and agave contemplated the nature of Xochipilli, the god dedicated to sacred words. Though Nahuatl had no exact term for poetry, it did have the “concept, [or] metaphor, ‘flowers and songs’ to indicate poetry,” as newspaper columnist Carlos Herrera Montero writes. Poetry embodied the “search for truth, for God, for the answers to the compelling and ancestral questions of humankind,” Montero writes. The purpose of poetry, according to Tecayehuatzin, is “to unfetter like the quetzal’s feathers / to spread out the Life-Giver’s songs . . . For within Heaven / from there / delightful flowers / delightful songs / come.” In his South American Journals (1960), Allen Ginsberg recalls that before poetry was recited in Boston and New York, or even Mexico City or Buenos Aires, it came from “Cuma, Chichen Itza, / Uxmal, Palenque, Machu Picchu,” the recitations of all those who “have lived in these dead cities.”

The category of “poetry” is a Western invention, like “religion” or “philosophy,” but in the “songs and flowers” of the Aztecs was something every bit as potent as the Orphic lyrics or the Homeric epics. Aquiahuaztin, who participated in that synod of Aztec poets, defined verse as “Intoxicating flowers . . . for the words of God.” Sixty years before Cortez overthrew Montezuma and conquered Tenochtitlan—a city that the conquistador Bernal Díaz del Castillo described as having “such wonderful sights, we did not know what to say, or whatever what appeared before us was real”—the poets of Huexotzinco assembled an ars poetica. The Serpent and the Fire argues for an expansive American poetics in the full sense of that adjective, gathering verse (or what its editors classify as such) from Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson, but also from Rubén Darío, José Martí, Aimé Césaire, and César Vallejo, as well as reproductions of neolithic cave paintings, transcribed glossolalia, and Indigenous oral texts. Rothenberg and Taboada remind readers that from Tierra del Fuego to Nunavut, America has always meant more than just the United States.

The collection also underscores the fact that poetry in America did not begin with Anne Bradstreet or Edward Taylor, nor even with Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz or Garcilaso de la Vega. It began in the shadow of the Puebla mountains and earlier. As the Nicaraguan poet Rubén Darío wrote in 1896, “If there is a poetry in our America, it is in the old things, in Palenque and Utalan, in the legendary Indian, and in the courtly and sensual Inca, and the great Moctezuma on the golden seat.”

The Serpent and the Fire is the last of Rothenberg’s anthologies, published shortly after his death at 92 last year. Its heft is a fitting culmination to his influential career as a poet and editor who, along with the anthropologist Dennis Tedlock, first defined the discipline, methodology, and approach known as ethnopoetics. Drawn to the sound experiments of early-20th-century avant-garde movements such as Dadaism and Surrealism, and to the strangely congruent field recordings of shamans and healers from various Indigenous traditions, Rothenberg and Tedlock (among others) recontextualized the entire history of poetry—and the practice of it as well. By literally returning to the archive and dusting off field recordings and prose transcriptions gathered by anthropological luminaries like Franz Boas and Ruth Benedict, Rothenberg transformed ethnographic notes into poetry. By translating pauses, tone changes, or volume alterations into line breaks and unusual typographical arrangements, he emphasized the distinct rhythmic and lyrical aspects of everything from tongue speaking to ecstatic trance. Rothenberg converted prose back into what was always poetry. In a 1975 interview, he argued that the “domain of poetry includes both oral & written forms” because “poetry goes back to a pre-literate situation, that human speech is a near-endless source of poetic forms, that there has always been more oral than written poetry, & that we can no longer pretend to a knowledge of poetry if we deny its oral dimension.”

A commitment to poetry’s aurality and orality as more central than syntax or meaning defined Rothenberg’s aesthetic. When compiling an anthology, he relied less on simple discernment than on an exultation in the madcap joys of juxtaposition. In any Rothenberg anthology, orally preserved Lenape creation myths could be printed next to work by Gertrude Stein or William Carlos Williams, the better to show the shared practice of poetry across humanity. Starting with Technicians of the Sacred: A Range of Poetries from Africa, America, Asia, Europe, and Oceania (1968), which effectively recategorized a bevy of traditions whose literature was long reduced to the “anthropological,” Rothenberg performed a critical function analogous to the museum curator who removes an African statue or a Native American headdress from the natural history museum and places it in the art gallery. Poems for the Millennium: The University of California Book of Modern and Postmodern Poetry, an initially two-volume set co-edited with Pierre Joris, was later followed by three additional volumes that, among other subjects and co-editors, focused on the 19th century and was a masterpiece of the anthologist’s art. An unparalleled achievement of poetic editing, which encompassed movements as varied as continental Romanticism and Caribbean Negritude, Chinese Misty Poets and American Language Poets, the thousands of pages of the Poems for the Millennium series places texts conventionally acknowledged as poetry next to ethnographic material as a means of enacting resonance, and of proving that verse itself is humanity’s fundamental mode of expression.

Poems for the Millennium functions as a kind of anti-canon, the collection as consciously inexhaustive as it is massive, wherein the suggestion of a deep relation between Shaker chanting and sound poems or Ghost Dance shouting and Dada is a welcome invitation to contemplation more than completism. The Serpent and the Fire continues this tradition but focuses on the half of the globe Europeans ostensibly “discovered” in the late 16th century. Displaying a fascination with American Indian poetics presented in previous collections such as Shaking the Pumpkin: Traditional Poetry of the Indian North Americas (1972) and America a Prophecy: A New Reading of American Poetry from Pre-Columbian Times to the Present (1973), Rothenberg and Taboada curate a Hemispheric poetics that places America—in all of its complexity and contradictions—at its core. America is, after all, not one continent but two; it is not the United States alone but 34 other countries as well, Spanish and Anglo, Protestant and Catholic, African and Indigenous. The histories of North and South America are far more intertwined than those living in the broad country between Canada and Mexico are apt to admit, so that the anthology is a means of “viewing north and south together in a hemispheric and transnational vision of what ‘America’ has meant in the long, overall history of our hemisphere and the world.”

The Americas have always shared more with each other than they have with their Old World antecedents. Consider what united figures like Washington and Jefferson with Simón Bolívar and José de San Martín, for as historian Greg Grandin writes in America, América: A New History of the World (2025), “they shared a faith in the redeeming power of the New World, that America was more an ideal than a place.” The Serpent and the Fire demonstrates that utopian contention and proves that there has always been poetry in this place, as the Nahuatl symposium makes clear. But from the “discovery” of the “New World” on, there has also emerged a potent new poetics based in dynamic new identities. In many ways, Whitman’s belief from the 1855 preface to Leaves of Grass that the “United States themselves are essentially the greatest poem” is accurate as long as we remember that those states that are united refer not just to New York and California, Texas and Illinois, but also Canada, Mexico, Paraguay, Uruguay, Chile, Argentina, Brazil, Haiti, Jamaica, and Cuba.

“What then is the American, this new man?” the French-born writer J. Hector St. John de Crèvecoeur asked in Letters from an American Farmer (1782). The history of literature from Patagonia to Lake Hudson has been an attempt to answer that inquiry. Reading Rothenberg’s collection, there is the sense that the American may look like a European, or an African, or a Native American, but that they constitute a new people with a novel identity. “Come I will make the continent indissoluble,” Whitman emphatically declares in 1860, “I will make the most splendid race the sun ever shone upon,” but crucially this is a race defined not by physiognomy but by geography, not by genetics but by creed.

This is what the Franco-Guadeloupe creole writer Ernest Pépin claims in “A Saltwater Negro Speaks,” from 2001, when he answers “Why we’re here” by saying it was “To extend Africa / So it can have buds / In the new fields of the Americas / Maybe we’re here / To make the world round.” In his verse-prose hybrid Cane (1923), the mixed-race American Jean Toomer writes that “To those fixed on white, / White is white, / To those fixed on black, / It is the same, / And red is red, / yellow, yellow.” “Surely there are such sights / In the many colored world,” he asks, and famously responds that he’s neither white nor Black but simply an American. Notably, this is not the same as a conservative “color blindness,” which pretends that even if biological difference is nonexistent race doesn’t have a social effect; rather, it’s to say that an author like Toomer understood being an “American” as being something different from deigning oneself a European or an African, and that this identity was based in the very newness of the continents, even if that newness was itself mythic. This is what the Cuban nationalist José Martí expresses in Simple Verses (1891) when he writes “I come from everywhere, / Towards everywhere I go,” for all of America is the Mother of Exiles, because “I am art among arts / And in the peaks I am a peak.”

The history of the last half-millennium is a history of the denial of this identity, of a resistance to the omni-American experience that should unite rather than divide the hemisphere. A cursory understanding of US foreign policy over the last two centuries— from the Monroe Doctrine to the Mexican-American War, the Spanish-American War to the various juntas supported and coups enacted during the Cold War all the way to the genocidal policies of the current administration—should explain why the Chicana poet Gloria Anzaldúa, in Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza (1987), describes the borders separating nations as “una herida abierta,” that is, “an open wound,” where the “Third World grates against the fist and bleeds. And before a scab forms it hemorrhages again.” In his 1904 poem “To Roosevelt,” written to protest US actions against Colombia in the construction of the Panama Canal and addressed to the rough-riding presidential hero of the Spanish-American War, Rubén Darío castigates the cold, Anglo-Protestant United States as having joined the “cult of Hercules with the cult of Mammon; / and illuminating the way of easy conquest,” a nation that is the “future invader / of all.”

American nature is riven by contradiction between the north and south, expressing the duality of that Aztec deity-principle of Ometeotl conjured at Huexotzinco. The Dominican poet Aída Cartagena Portalatín, in Yania Tierra (1981), mourns how “They keep coming from the North / The pirates loot / Riches from Coffee / Sugar / Cacao / Gold / silver / Nickel / bauxite,” an extractive violation that rips the very entrails of the earth from the ground. There is understandable frustration among many other North and South Americans over how those in the United States apply the word American only to themselves, though with some irony it’s those in the United States who often forget that it’s they who are also American because they deny the fullness of that identity. “Mexican children kick their soccer ball across, / run after it, entering the U.S.,” writes Anzaldúa, for the fact is that people don’t cross borders, since such lines are nonexistent anyway, but frequently borders do cross them.

Given that reality, The Serpent and the Fire is the crowning achievement of Rothenberg’s already distinguished career, and one that couldn’t have arrived at a more salient time. In an era when a presidential adviser can tweet about desiring the genocide of 60 million Hispanic Americans, or when the Office of Homeland Security could operate a detention center on sacred Miccosukee and Seminole lands, Rothenberg’s anthology is an encomium for the complexity, the contradictions, the multiplicity, and the magnitude of the American people—of all the American people, whatever illusory border separates them. With that understanding, poetry is both deeply political and politics fundamentally poetic. Mapuche Nation Chilean poet Elicura Chihuailaf Nahuelpan writes as much in “The Key that No One Has Lost,” in which poetry is the “deep murmur of the murdered / the rumor of the leaves in the fall ... Poetry, poetry, is a gesture, a landscape . . . poetry is the chant of my ancestors / a winter day that burns.”

In his critical generosity and expansiveness, what Rothenberg understood is that America is the greatest poem because we’re still living in the ruptures of that “discovery” five centuries ago, of the exchange that in its horrors and traumas sutured together the two halves of the globe. He describes “this constant reinvention of America,” and that’s because the singularity of the Western Hemisphere’s discovery still reverberates like nothing else in our culture, since it still allows for the possibility that our world can be made new. The unveiling of this fourth part of the world, like something in Revelation, broke the monopolies of Europe, Asia, and Africa, for now a new people could be formed from all the peoples of the earth.

In her 1685 baroque vision “First Dream,” the nun Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz describes how America necessitated “Closing the luminous circumference,” how the remnants of the world “attained, at last, sight of the West . . . while the golden Sun / adorned our Hemisphere / with skeins of judicious light / dispensing their colors / to visible things, / and restored to outward sense, / their full operation / —keeping to more certain light, / the World illuminated.” All of this is mythic, but meaning is made in myths. What should be recalled is that America was always like Eden or Arcadia, but with the paradox that America is also real. A secret language thrums through the cultures of the New World that is built on a unity in division, where the greatest dramatic tension exists in the fissures and bindings within this endlessly regenerative assortment of lands. “No one will ever stop our flowers,” said the Aztec lord Ayocuan Cuetzpaltzin at that long-ago assembly, “no one will ever stop our songs.”

Ed Simon is the Public Humanities Special Faculty in the English Department of Carnegie Mellon University, a staff writer for Literary Hub, and the editor of The Pittsburgh Review of Books. A regular contributor to several publications, his most recent books include Devil's Contract: The History of the Faustian Bargain (Melville House, 2024), Relic (Bloomsbury Academic, 2024), Elysium: A Visual History…