The Color of Ideas

An introduction to the folio “E. Ethelbert Miller: Friendship Is What Keeps Us Whole.”

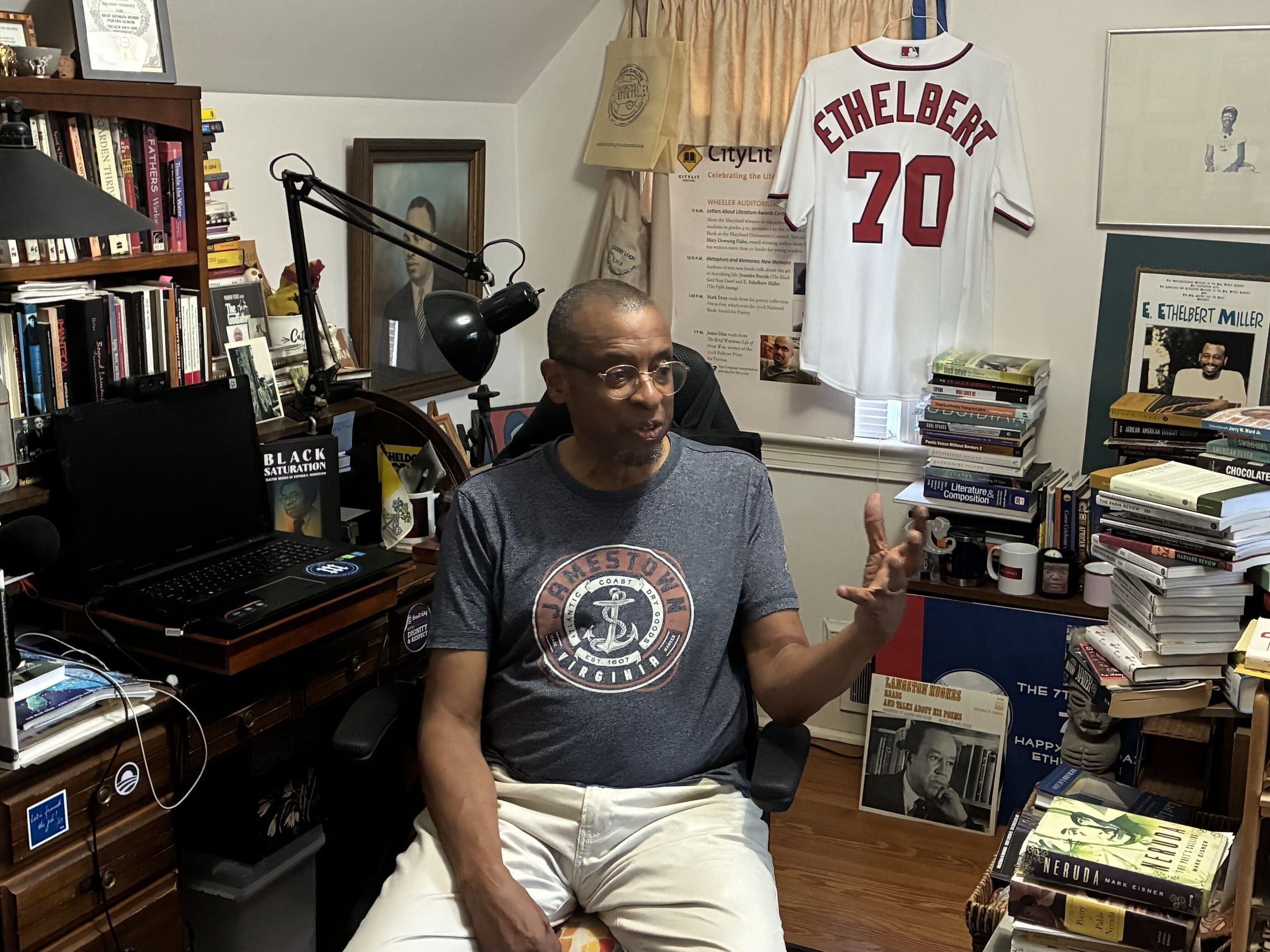

E. Ethelbert Miller in his home office, 2025. Photograph by Rafi Ellenson.

and hurricanes will come

and speak no English

—E. Ethelbert Miller, “Solidarity”

The son of a father from Panama and a mother with roots in Barbados, E. Ethelbert Miller was born in the South Bronx in 1950. At Howard University, he was born again, “baptized,” as he once put it, in the Black Arts Movement. A first-generation college student, he emerged from those waters committed to Blackness and Black history as traditions of thought, philosophies in the making, and practices of perception: ways of loving people, knowing people, and being a person in the world. Blackness for Miller was not biological or thematic or absolute, it was about the “color of ideas.” Because of his formative experience at Howard, Miller has spent his life “in search of color everywhere”—to borrow the title of his award-winning anthology of African American poetry, which itself was borrowed from a poem by his friend, the poet Elizabeth Alexander.

At Howard, this search began with his mentor, the critic Stephen Henderson. He learned a great deal about poetry’s role in Black world-making and community building from Henderson. A self-described “literary activist,” Miller is a committed servant and administrator of Black institutions. For forty years, he directed Howard’s African American Studies Resource Center. In 2015, when he was dismissed from his position, Elizabeth Alexander wrote: “Generations of writers—myself included—have made the trek to see him as budding young creative people committed to the art of the African diaspora. His generosity is legion.” Since then, Miller’s generosity and commitment have remained steadfast. He continues to work as an anthologist, memoirist, blogger, editor, ambassador, and adroit go-between. As the host of several TV and radio shows, he has interviewed countless writers and scholars including Amiri Baraka, Toi Derricotte, Tyehimba Jess, Edward P. Jones, ,Tony Medina and David Mura. For a decade, he was coeditor, with Jody Bolz, of Poet Lore, the nation’s oldest continuously published literary journal. He also became a founder of the Humanities Council of Washington, DC, and served as commissioner for the DC Commission on the Arts and Humanities.

Above all, Miller is a sustainer of poetry. An ardent believer in Martin Luther King Jr.’s Beloved Community, Miller demonstrates that to love poetry means to love oneself and others—and the world—enough to defend and remake them, and be remade by them in turn. June Jordan was another poet committed to King’s “radical revolution of values,” and Miller’s onetime lover and longtime friend. In “Grand Army Plaza,” her poem dedicated to Miller, and which Miller answered with a poem by the same title, Jordan memorably writes that we “survive our love/because we go on//loving.” Miller’s and Jordan’s poems addressed to one another are a record of their dedication to the project of making “revolutionary connections,” as Jordan defined them,

between the full identity of my love, of what hurts me, or fills me with nausea, and the way things are: what we are forced to learn, to “master,” what we are trained to ignore, what we are bribed into accepting, what we are rewarded for doing, or not doing.

—From “Notes from a Barnard College Dropout”

After Jordan’s death in 2002, Miller has continued to make these abiding connections. In “Some of Us Did Not Die: Remembering June Jordan,” Miller quotes a speech Jordan gave celebrating King’s life. “Is there reason for hope?” Jordan asked the audience. “Is there anywhere a trace, a phoenix of revolutionary spirit consistent with Dr. King’s preaching and true to the democratic, coexistent values of Beloved Community?” She answered her own question unequivocally: “I know there is. It may be small. It may be dim. But there is a fire transfiguring the muted, the daunted spirit of people everywhere.” As this folio attests, Miller’s tender, humorous, affirming, undeniable poetry burns with this transfigurative fire, calling us to remembrance and action.

Miller’s later writing—including, notably, his trilogy of baseball poetry books—often turns to the entwined histories of baseball and freedom struggles to work through what revolutionary connection means for those of us living through the crises of the present. The critic Emily Ruth Rutter has aptly described baseball as a “mode through which Miller confronts past failures and imagines the possibilities of an equitable American society as well as his own place within it.” Miller’s work, Rutter concludes, articulates “a way of life predicated on an understanding of love not as a saccharine sentiment but instead as a commitment to mutuality and the politics of inclusion.”

I first read Miller’s poems in the groundbreaking anthology ¡Manteca!: An Anthology of Afro-Latin@ Poets edited by Melissa Castillo-Garsow, which included his poems “Panama” and “Spanish Conversation.” To approach Miller as an Afro-Latinx poet clarifies his proximity to and simultaneous distance from the Black Arts Movement and helps us hear what Miller calls the “language work” of his poems. As Miller explains in an interview with Krista Tippett for NPR’s On Being, language work entails the recuperation and defense of the vocabulary of Black freedom struggles, which sometimes seem so encroached upon, so co-opted, so appropriated and distorted, that the historical meaning of those struggles feels altogether lost. Language work, Miller adds, means using language to perceive through the veil of discourse not just “the hurt, the pain, but ... the joy and the celebration.” And to want to be “taught that music.”

a dark skin woman asks me

if i’m from angola

i try to explain in the no spanish i know

that…

can hold us together

i watch the women

bead their hair

each bead a word

braids becoming

sentences…

dogs sniff among the ruins

the graves are multiplying

At the same time, Miller’s language work creates soundworlds of play and possibility not typically part of the conventional narratives that understate the Black Arts Movement’s Caribbeanness and its ideological and aesthetic diversity. It’s no accident that one of Miller’s earliest elegies is for the Guyanese radical intellectual, Pan-Africanist, and historian Walter Rodney. Miller’s great elegies for Malcolm X came later. Indeed, Miller once remarked that the grounding events of his childhood were neither the assassinations of Martin, Malcolm, and JFK nor the heaving violences of Civil Rights struggle, but, as he writes in the unpublished poem “¿Yo soy de?,” the rhythms of a childhood in which “Puerto Ricans fed my ears sweet Spanish” and “my hips learned the language that translated to my feet.”

The seething presences of the African Caribbean abound in Miller’s work. “Black Reality: The Last Haiku,” the final poem in “Haiku Series,” reads:

black power is black

hurricanes changing the world

this is not a dream

Miller’s “Haiku Series” revisits icons of the freedom struggle—Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, and Rosa Parks—then shifts to the anticipation, abstraction, and reordering powers of everyday Black life. This move from the familiar tropes of dream and deferral to the multifarious plenitude of “Black Reality” enacts a kind of joyous remonstration. Miller’s inventive use of the haiku form braids together the rich tradition of haiku by Black poets like Lewis J. Alexander, Robert Hayden, Richard Wright, Jordan herself, Sonia Sanchez, Alice Walker, Lenard Moore, James Emanuel, and Kwame Dawes, among others, with the hurricane, that quintessential Caribbean form.

As Kamau Brathwaite observed decades ago, the poetry of Black hurricanes swirls and roars across the “mighty curve” of the African Americas. From the work of Zora Neale Hurston and Miller’s friend Nancy Morejón to Safiya Sinclair and Joshua Bennett, this poetry urges us to re-hear, re-member, re-call, and re-sense the daunted spirit of people everywhere. Because it springs out of what Castillo-Garsow calls “the overlapping and intersecting expressions of Afro-Latin@ consciousness,” Miller’s searching poetry, full of the possibilities of revolutionary connection, challenges the popular narratives that rebrand the history of African Americans into yet another exceptionalist story.

The poet Reetika Vazirani, another longtime friend, once remarked that Miller has been a “guiding light” for poetry readers everywhere. “God bless you mister e,” Vazirani affectionately wrote at the end of a letter to Miller:

Your lowercase is so infectious, your crazy linebreaks are so infectious, your breaking all the rules is so infectious though I think you have gone inside the inside of william carlos williams’ red wheelbarrow and have come out with e ethelbert millers joy to the world.

So much depends upon this joy, that “rigorous emotion,” as Ross Gay calls it. With Miller’s poetry we go searching “inside the inside” of this upturned wheelbarrow and come out the other side refreshed by the reordering force of joy—Black hurricanes of it, revolutionary connections of it—that we might survive our love again.

E. Ethelbert Miller at Common Concerns bookstore, Washington, DC, April 19, 1990.

Photograph by Rick Reinhard.

E. Ethelbert Miller with Naomi Shihab Nye, Sept 2015, at the National Book Festival in Washington, DC. Photograph by passerby.

E. Ethelbert Miller with W.D. Mohammed, 1983, photo by Julia Jones.

The letter from Reetika Vazirani to E. Ethelbert Miller that is quoted in this essay is from the Reetika Vazirani Papers, Special Collections Research Center, William & Mary Libraries.

This essay opens the folio “E. Ethelbert Miller: Friendship Is What Keeps Us Whole.” Read the rest of the folio in the November 2025 issue of Poetry.

Scott Challener is associate professor of English and Dean of the Graduate College at Hampton University. His poems and essays appear in ASAP/Journal, Berkeley Poetry Review, Contemporary Literature, Gulf Coast, Lana Turner Journal, Los Angeles Review of Books, Mississippi Review, OmniVerse, Post45 by Contemporaries, The Langston Hughes Review, The Rumpus, The Nation, and other publications.