Like Fireflies Hanging from the Tamarind Tree

On Irma Pineda's trilingual Stolen Flower.

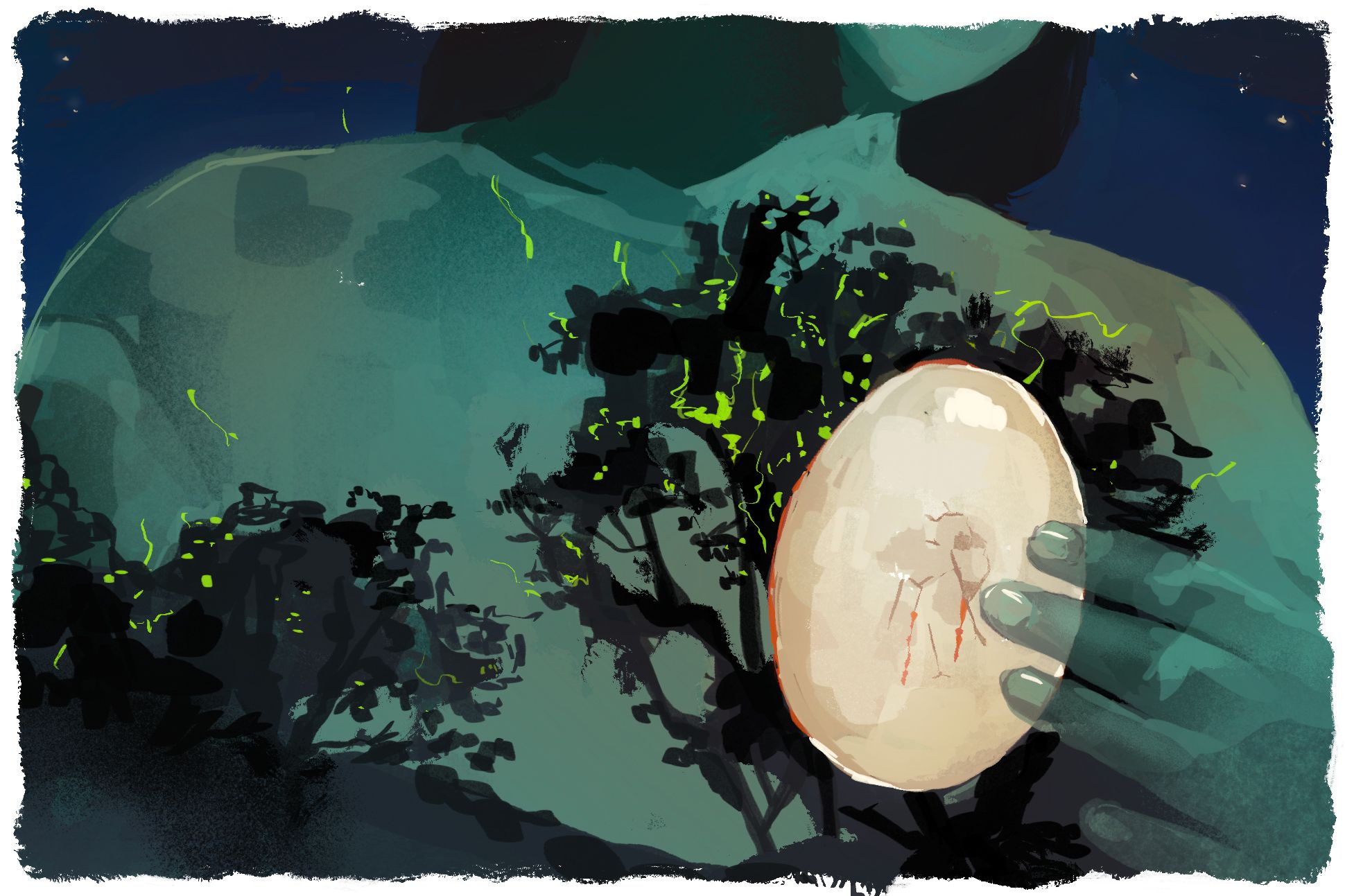

Artwork by Carson McNamara

Early in Stolen Flower, a collection of poems by the Isthmus Zapotec poet and activist Irma Pineda, newly translated into English by Wendy Call, a speaker recounts an exchange with an unnamed second person who asks, “Where is the precise place / that a man’s heart might be split / before it cracks open / like an eggshell on the hearth?” The you asking this question is young, with a “green-stemmed voice,” and seemingly alone: the poem ends with “thousands of footprints” that “lead away on the path / without even a moan in reply.” It takes a long time before Stolen Flower offers an answer to the interlocutor’s question, but when it does, Pineda returns to the image of the cracked eggshell. “Hate is enough to break” a man’s heart, she writes:

it’s not the time that’s passed

nor the dead girls

nor the accumulated pain

nor the people we’ve lost that kill us

Just that small moment is enough

for sleeping rage to stretch its arms

yawn let out a tiny moan

and we notice a heart splitting

like an eggshell by the fire

Stolen Flower deals at length with heartbreak. Published 12 years ago in Mexico, in both Spanish and Didxazá, a version of Zapotec, it’s a poem cycle, or perhaps a novel in verse, that reacts to the 2007 death of Ernestina Ascencio Rosario, a 73-year-old Nahua woman who, while working in her cornfield in Veracruz, was raped by a group of Mexican soldiers—between four and 11 of them, according to the World Organization Against Torture—and left to die. For years, the Mexican state accepted no responsibility (in January 2025, it participated in an Inter-American Court of Human Rights hearing in which the Court called for a renewed and complete investigation of Sra. Ascencio’s death)—an irony given that in 2023, Mexico’s public education ministry rereleased Stolen Flower and distributed it to 12,000 libraries.

Pineda aims her poetry straight into gaps like the ones the education ministry’s actions reveal: mismatches between state narratives and the reality everyone else knows to be true. Her subject is not just Sra. Ascencio’s death but the invasions, abuses, and terror that Indigenous Mexicans have suffered at the military’s hands for generations, a story Pineda knows intimately: the Army disappeared her father, Indigenous rights leader Víctor “Yodo” Pineda, when she was four. Her poems, all untitled, conjure brutality and violence, assaults against bodies and the earth, in a poetic voice that is arrestingly clear. At times, she directly addresses soldiers like the ones who attacked Sra. Ascencio and took her father. Some poems include photographs of the military embedded in the text. Others feature photos of Mexican civilians like the book’s speakers, amplifying its collective voice. But the speaker in Stolen Flower is much more often an I than a we, and the book’s strongest poems are those written in first person that say, insistently and consistently, what Pineda knows to be true. Such reporting, whether it takes the form of activism, court testimony, or literature, is one of the few tools individual citizens have against government denialism—and a powerful one. “This is war, / we told ourselves, ” Pineda writes in Stolen Flower, “and sharpened our words.”

Pineda’s poems, many of them fewer than ten lines long, capture not an “accumulated pain” too big to comprehend, but fleeting slices of emotion or agonizing experiences, such as the moment in which a dying woman tells her killer, “When my spirit rises / it will return to this tree / to stare at your fingerprints.” In both the Spanish version and in Call’s English translations, every line is easy to speak aloud, owing, perhaps, to Pineda’s own relationship to Didxazá. In a brief preface to a 2005 selection of her poetry in the Mexican journal Debate Feminista, she writes that her parents, Didxazá speakers, learned Spanish by force, then decided to speak it at home to their daughter, hoping that Spanish would “facilitate my inhabiting the world.” But when a young Pineda left the house each day, “life burst into Zapotec.” She learned to “dream and laugh in Zapotec, to move my thought from one language to another, like changing channels.” Her parents, accepting this, began to raise her bilingually. When she left her hometown of Juchitán de Zaragoza—to which she has since returned—she switched back to speaking mainly in Spanish. “To keep my heart from withering,” she explains, “I began to make poems that I read to the wind, so I wouldn’t forget the sound of Didxazá, and wrote in Spanish so others would know what I wanted to say.” (All translations of this piece, which is in Spanish, are mine.)

In her introduction, Call, who reads and studies Didxazá, explains that over the course of her 16-year collaboration with Pineda, the two of them have developed a process that relies equally on the Didxazá and Spanish versions of each poem. “Because I can read both originals,” Call writes, “I have two paths into English. Some lines of my English translation might seem a bit distant from the Spanish because I have chosen the Didxazá path.” This shuts down any impulse a Spanish-English bilingual reader might have to perform the sort of gotcha-reading that, sadly, often passes for translation criticism—and that, in this case, would risk erasing Zapotec culture. In one poem, for instance, the speaker tells the invading soldier,

this forest is our home

it is our mother and daughter

we know every inch of her skin

just by smelling her scent

she doesn’t want you inside her

and so

you will have no peace.

The Spanish verse that corresponds to she doesn’t want you inside her is “ella no te quiere en sus entrañas,” a less sexual and more visceral phrasing than Call’s English. But sexuality is present elsewhere in the collection, and “she doesn’t want you in her guts” would ring oddly in English, undermining the poem’s plainspoken cadence. In Stolen Flower, the presence of the Didxazá is a reminder that the poem has a rich subtext that may escape the English- and Spanish-speaking reader.

Pineda’s choice to write simultaneously in Didxazá and Spanish—that is, in her own colonized language and the language of her people’s colonizers—is very present in Stolen Flower, which can be seen as a conversation across, and between, those tongues. Each poem is printed in English, then Didxazá, then Spanish, a format that asks most American readers to engage in some way with at least one language we don’t understand. Many, of course, won’t. It’s easy to allow one’s eye to run over unfamiliar text, or to simply flip past it. But to do so would be to ignore what animates Stolen Flower, in which the presence of the text in Didxazá is a visual reminder of both Pineda’s exchange with the wind and her trilingual process with her translator. In her introduction, Call explains that the two of them discuss every line rigorously, with Call sometimes re-translating her English verses into Spanish in order to demonstrate her choices to Pineda. This style of working—which, I should add, is unusual: many writers collaborate with their translators, but rarely to this degree—may well augment the direct, almost conversational tenor of Stolen Flower’s poems. Even Pineda’s most elaborate similes, like the memory of a night sky “like fireflies hanging from the tamarind tree,” are written in straightforward words and syntax.

Trees are everywhere in Stolen Flower. So is the color green. Paying attention to their repeated appearances leads to the heart of the book’s most difficult, if imagined, dialogue—between its Indigenous speakers, often symbolized by nature, and the fatigues-clad soldiers occupying their land, referred to throughout this collection as “men in green.” “Your green is a disguise telling lies,” writes Pineda, insisting “We are the ancient tree that holds all history / in its every branch.” Elsewhere, we read of the devil climbing up to earth in “leafy clothes / disguised as a child of the earth,” but Pineda does not go so far as to call the soldiers themselves devils. In fact, the only time a color other than green appears in Stolen Flower is when a speaker tells a soldier, “we are equals / children born of red earth.”

This conviction shines through all of Stolen Flower. Pineda’s anger at the Army is, like everything else in the book, utterly clear, and yet she never condemns individual soldiers. Instead, when a soldier is addressed in a poem, the goal is always to “push the huge stone of his body,” to press him toward his lost humanity. But the soldiers don’t listen. They refuse conversation. They’ll only “heed the voice / that has taught you to earn your daily bread.” Pineda’s speakers express anger at the soldiers for this without pushing them away; one tells a soldier that “though he is the hand of evil / he too / is my brother.”

Call’s translation of Stolen Flower arrives at a critical time in the United States. The hand of evil is everywhere in our communities. In Washington, DC, where I live, National Guardsmen lurk in Metro stations and ICE agents snatch my neighbors from work vans, street corners, libraries. While

Stolen Flower speaks directly to its own place and moment, with the original Didxazá on the page a reminder of how rooted the collection is in Oaxaca, the Spanish directly beneath the Didxazá serves as another kind of reminder, insisting that we can’t ignore the hand of evil, that we have an obligation to speak to and about it. Otherwise, the voice that teaches us to prioritize our personal gain above all else—the one that teaches you “to earn your daily bread”—will be the only one we hear.

Lily Meyer is a translator, a critic, and the author of the novels The End of Romance and Short War.